Time for that 'where should Design live in your organisation?' conversation

Where does Design live in your organisation? The answer to that is likely different depending on your Design discipline. If you're a visual Designer it's more likely you sit within Marketing. If you're a UX, UI or Product Designer it's more likely you'll sit either in Engineering (if you're working in an early stage company or on an Engineering-heavy product) or in Product (if you're working in a later stage company or a consumer or customer focused product). It's highly unlikely - whatever your discipline - that you'll sit in a Design vertical that reports directly into leadership.

There are a range of options when considering where to place Design in an organisation, and the most obvious places are within existing 'leadership' verticals. Most organisations tend to have one or more of these leadership verticals, which are headed by someone who reports into - so that's nearly always one or a combination of; Product, Engineering, Marketing or Operations.

There's a long history of Designers bemoaning the need for Design verticals, and the need for a 'seat at the table' - whatever that really means. In truth, there are some good arguments for placing Design in it's own vertical, just as there are good arguments for placing it inside other verticals - however in most organisations, Design is seen as incumbent and a service of larger needs. The reasoning here is that most organisations are founded and focused on solutions - on an engineered / technical solution, a solution to a customer need or problem, or a brand / communications / content solution. In these environments, typically, Design is seen as an executor of strategy, not the creator of strategy. In engineered solutions, Design might build patterns that allow check-out processes through payment integrations. In customer / product solutions, Design might craft and test empathetic and user focused flows. In brand or content solutions, Design will visually execute narratives and stories. In start-up organisations, these various solutions usually play out through the early stage hiring of a generalist Designer with a singular focus on execution. Later that organisation will employ a vertical leader - who then is charged with overseeing the Designer. The Designer then ends up working within that vertical.

One reason that Design performs these somewhat subservient roles is, in most organisations, Design is not really that tangible. There are many other reasons, sure, but it is very rare that Design's impact in an organisation is measured beyond basic output. Engineering can use uptime stats, Product can use bounce-rates, Marketing can use KPIs and click-throughs, views and likes. However, even beyond these basic metrics, it's rare to even see Design represented in higher level strategic metrics such as OKRs - or for those who don't operate OKRs - basic quarterly strategies.

Why is that? Is it because Design is just perceived as a subjective output by non-Designers? Or is it because Designers do a bad job of making Design non-subjective? If it's the latter, then it's hard to blame them when you look at the details. In larger organisations, Design discipline can incorporate UX, visual, animation, commission, narrative, copywriting, experiential, editorial, photography, video, branding, agency management - there's likely many more. Aligning these hugely varied roles, and with them their varied outputs, and often an orgs vastly differing opinions on those outputs and their 'perceived value' - makes managing the full gamut of Design a highly complex proposition. So complex in fact that it's very rare to find a Design leader who not only operates with this level of breadth, but also is even permitted that level of remit.

Even in smaller orgs you'll likely have a combination of visual / brand and product focused design roles. The complexity in leading or coaching even those two disciplines can be vast - running critique across visual and brand, coaching those skillsets - yet also running equivalent critique in UX, UI, user behaviour and research and coaching a completely different range of skillsets - is one hell of a context switch.

So surely with such a context switch, and with such a level of complexity, it makes complete sense to align design disciplines with their relative organisations.

The case for Design inside existing leadership verticals

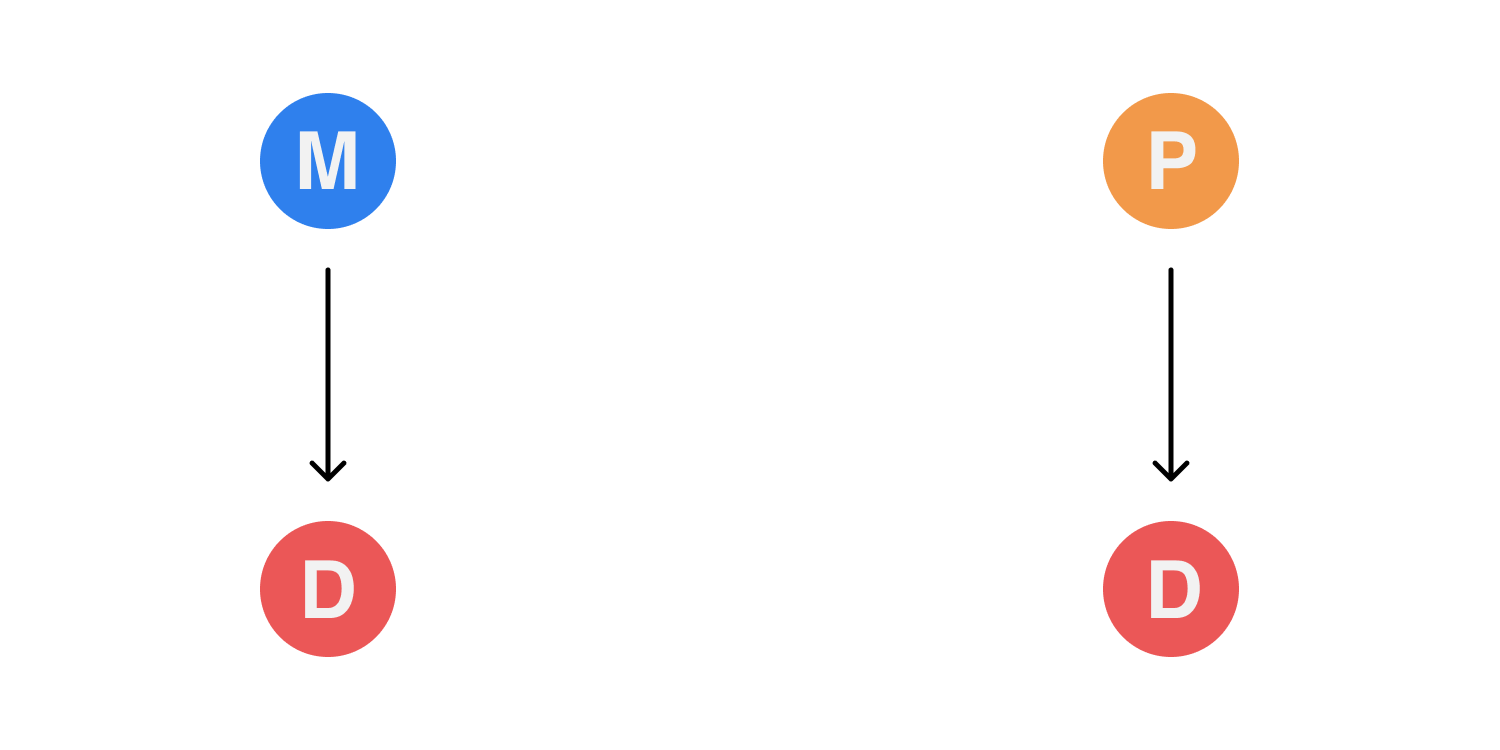

Most organisations will likely run Design in some variant of this model. In a typical scenario Design sits inside Marketing and inside Product. In Marketing the Design team will be represented by a Creative Director (or equivalent leader) who reports to the VP, Head or Chief Marketing Officer. On the Product side, the Design team, most likely made up of Product Designers, will report to the VP, Head or Chief Product Officer.

Pros

Splitting Design disciplines into their relevant verticals means that the Designers inside those verticals have a distinct culture and context that's aligned with their output. In Marketing, Design will entirely cohabit with visual, story and content, and the workflows and strategies day-to-day are likely understandable within that ecosystem. In Product, Design will cohabit with research, community, and product owners - their workflows aligned to Engineering and will likely incorporate agile practise.

The benefits of these focused contextual ecosystems is the ability to quickly mobilise teams and get shit done. From a Design management point of view, line management and coaching is easier as the disciplines are inter-connected and share a common base. Design as a service in these environments also means that Designers can coordinate with their relevant peers to get behind broader reportable metrics and outcomes.

Cons

With Design inside verticals, Design does, however your look at it - become a service, and the position of Design within that vertical can become quickly determined by the approach to, or understanding of, Design by that vertical leader. This means that, even with a Design management layer below that vertical leader, the Design environment, or the concept of Design, is set culturally by either the leader for Product or Marketing. With that leader usually not being a Designer, there is then a conflict in communication, leadership and coaching as the vertical lead tries to manage a discipline they don't fully understand, and they will likely form desire lines in communication with other Product people or other Marketers.

This disconnect means that a Design leadership role within a vertical requires constant mediation of communication, and also the upward management of both design expectation and design education. For verticals that don't support a Design leadership role, the onus on design culture, leadership and coaching inevitably falls on the vertical leader, and in those environments the success of design falls on that leader having either the experience of understanding of design to maintain the status quo and both enable and coach the design talent in that vertical to a high standard. In verticals that don't recognise Design leadership, typically the chance of attracting talent drops, as does the chance of retaining that talent.

Another issue with this model is that is silos Design within verticals. In some organisations this has limited impact, but in organisations where Marketing is a key player in driving and on boarding users into Product, those silos can quickly begin to show themselves. Issues like copywriting, brand appropriation, tone and consistency can suffer, and those issues can be difficult to solve as Design fails to form the core linkage and the success relies on the two vertical leaders not only communicating at the right level, but also aligning their Design services to execute on the same strategies through varied disciplines - disciplines that the vertical leaders won't effectively understand in any great depth.

The case for Design inside existing leadership verticals, with joined Design leadership

This effectively places Design within the leadership verticals (as in the previous case), but assigns a Design leader to oversee and lead Design cross-vertically. In this instance it's likely that a VP or Senior layer is created that reports to both the Marketing Lead and the Product lead with the intention that the VP / Senior can coach within both verticals and manage up to both vertical leads. On paper this look best case - the VP oversees the Design leader in each individual vertical, and provides context and communication between the two Design teams, while also maintaining a cross-vertical Design culture and apply consistency in output.

Pros

The VP / Senior layer applies increased communication around Design and because of this there is an increase in culture and consistency. In organisations that require a blurred line between Marketing and Product, or Product and Brand, this layer brings a lot of impact into the quality of the various Design outputs. There is also an increase in Design education, and while the VP / Senior coaches the various Designers in their cross-vertical team, there is the opportunity for the vertical leads themselves to gain insight into Design, and it's requirements beyond the various in-vertical outputs. In reality the VP / Senior role provides a Designer who is not a direct contributor, but has the oversight to provide advisory - their abstracted role gives them space to think and balance requirements, which while key to coordination of staffing and communication, provides the vertical leads with cross-vertical Design strategy which they can incorporate into their own vertical leadership.

Cons

The VP / Senior removes the need for vertical leads to manage and coach Design inside their verticals, but it places the VP / Senior in a relatively tough position, executing against dual strategies and acting as a singular conduit. With any organisational setup which relies on a singular linkage, that linkage inevitably becomes a point of weakness. The VP / Senior is responsible for not only Design culture, but for bridging disciplines, cross-criticism, cross-context and for coordinating strategies from two verticals, which often might have competing needs. The VP / Senior is therefore beholden to the clarity and reality of the individual vertical leaders strategies, without a direct strategic input of their own. Depending on the organisation and it's complexity, this can place the VP / Senior in a position where they are largely reactive in their execution, advisory for decision making, as they attempt to weigh up, from line managers, the best decision to make. This can of course be mitigated by either 'managing up' to those leaders, or applying a communication strategy that attempts to align the two channels - however it's highly likely that the VP / Senior will, purely through he nature of the contextual differences of the various verticals - find themselves between a rock and hard place. They may find that the vertical leaders default to - or subconsciously - revert to line managing within the vertical, effectively cutting off strategic input and making the VP / Senior contextually irrelevant. This isn't inevitable, but the VP / Senior is one layer of management more than the 'get shit done' scenario described previously, and unless they find themselves involved in every decision in every team, align to every strategy and understand every context - they may find themselves in danger of becoming redundant or - worse - part-informed and therefore ineffective.

The case for Design existing as it's own vertical

Much is made of this ideology in Design circles, likely because it oozes control and enablement. But to execute this type of organisational change requires more than simply placing Design in a vertical - and this is why it's such a rare entity.

There is also quite a bit to be discussed about Design taking on such a heavily contextual role and - as is often the case - such a janitorial one. Most vertical leads are operational roles at their core and are focused on strategy, insight and alignment. Design not so much. Designers, regardless of their leadership component, usually try to incorporate some element of independent contribution to their day to day. That might read like a cliche, but it's largely a by-product of Design as a discipline. Because Design is a craft, it is taught, learnt and gained through the process of doing. Its ultimate execution may be quantitively or qualitatively led, but the process of Design, the thinking, the skill, the coordination of thought and action, is directly empowered and built through contribution. Managing contributors then can be difficult, especially if the Design leader does not have the necessary insight or knowledge into that craft. That insight and knowledge allows for hiring, coaching, enablement, context and better communication cross-discipline. To that point if a Design leader is to run a Design vertical, then to perform better than a Marketer or Product leader, they have to provide value to the organisation - through that insight into craft - by building strategic tangibles. If that sounds familiar, then it is - most Engineering teams mirror this to some extent. Where Design differs from Engineering, however, is in the sheer scale of disciplines it represents, and therefore the sheer amount of context required by Design leaders of a wide variance of craft.

In truth, however, the reasons that Design isn't often seen in its own vertical is more to do with how it's perceived - and that perception is driven by Design's need for the individual contributor and the practice of craft. Craft doesn't seem strategic, it seems reactionary. It doesn't seem inclusive, it seems closeted. The decisions made in the process of crafting a Design solution are not easily exposed or understood by others - and this is largely proven through the presence of subjective critique around Design. Subjective critique is usually the sign of miscommunication, or a misunderstanding of either how Design critique works, or where Design is placed within the organisation. Either way it's usually a symptom of a lack of Design education being delivered into the organisation.

Design existing as its own vertical solves this to a point. It creates a level hierarchy for Design to coexist alongside Product, Engineering Marketing and Operations - and with that, craft, critique and Design education is brought into definition across the leadership.

Pros

With Design reporting into the leadership level, there's a clear acknowledgement that narrative, craft, aesthetic and usability are accepted as being on par with - and also form part of - the strategy of the organisation. With Design able to operate inside - and independently - of other verticals, end to end narratives, consistency and creative innovation can now exist cross-discipline and there is the opportunity, depending on the Design leadership, to have huge wide reaching impact and penetration across the whole organisation. Design therefore becomes, rather than an occasional empathetic workshop facilitator, a thought leader with the ability to move into any vertical. Design is placed in a position where its hard-won skillsets related to problem solving and diligence can be refracted back onto the organisation itself - this isn't a Design thinking exercise design to empower the executive, but rather a constant revision of service Design within the organisation - Design begins to Design the organisation as a whole. Design talent becomes easier to hire, develop and retain, as thought leadership and Design strategy resonates within the organisation, rather than just in 'maybe one day' Medium posts, 'attract the talent' organisation blogs or 'big sell' conference stages. Design talent onboard into a vertical of their own, able to discover new disciplines, talk a common language and culture and therefore create more meaningful critique. Storytelling improves, Design quality improves, and the organisation shifts positively through the hard-won Design skills of the Design vertical becoming part of the organisations DNA. The organisation now approaches its problems using Design as a peer and trusted advisor.

Another benefit is within the Design leadership and management of the vertical itself. A dedicated Design vertical allows for management structures to be created that are perfectly suited to a variety of Design disciplines. Design management in this environment becomes less about assigning management layers to cross-communication roles with other vertical leaders, but allows the Design vertical to appoint management structures that encourage coaching, contribution and skill transference with the Design culture.

Cons

With Design having a broader remit, and encapsulating a wide variety of disciplines, there is a real pressure on Design leaders to oversee not only multiple disciplines, contribute and coach, but also lead design on an organisation level. Depending on the complexity of the organisation, those skillsets and disciples could be so diverse for some Design leaders that they become unable to effectively embrace those disciplines and skillsets effectively in the Design vertical. Additionally the sourcing of such a diverse Design leader can be a very difficult thing to do, especially for organisations that might not be renowned for their Design output. It may also be the case that in some organisations, hiring the required level of generalist to lead the Design vertical might actually handicap the organisation if they have strong requirements in one specific Design skillset. This could see a Product focused organisation with a more limited Marketing remit struggle to hire a generalist Design leader when they really need to hire a hyper-skilled UX Design leader - how does a leadership team hire the right Design leader to run a Design vertical when they might not be qualified enough to hire the right Design leader?

There are other downsides of course, and they mainly involve elements of disruption. The cultural shift for some organisations to bring Design into the leadership is just too vast for them to actually action. Changing perception of Design can be a tough thing. Giving Design the room to form its leadership role can be seen as high risk - and the reality of there being few organisations that have moved Design into leadership, the lack of 'proof' in wider business culture of it having true impact - means that for many, Design as its own vertical has a big question over it's added value.